Textural Dislocations of the Fourth Gospel

The references below provide an overview of commonly observed dislocations and interpolations (redactions) of the Fourth Gospel

C.K. Barrett, The Gospel according to St. John, Westminster Press, Second Edition, 1978, p 21-23

Theories of Displacement and Redaction

It is moreover true that when the gospel is read through, in spite of the general impression of unity, certain indications of disunity and dislocation are found. The narrative does not always proceed straightforwardly; some of the connections are bad, and sometimes there are no connections at all. Occasionally, a piece seems to be out of its proper settings. It is on the basis of these observations that theories of accidental displacement of parts of the gospel, and of editorial redaction, have been founded. (p.21)

A few suggested displacements will be mentioned, most of them going back to the time before Bultmann’s consistent carrying through of the inquiry, but taken up and elaborated by him.

(1) John 3:22-30, Which seems to interrupt the Nicodemus discourse (John 3:31 follows upon John 3:21), should be removed and placed between John 2:12 and John 2:13. This change also improves the itinerary, since Jesus, in Galilee in John 2:1-12 is brought εις την ‘Ιουδαιν γην (John 3:22) before going up to Jerusalem at John 2:13.

(2) Chapter 6 should stand between chapters 4 and 5. Again the itinerary is improved. As the gospel stands, Jesus is in Galilee (John 4:54); goes up to Jerusalem (John 5:1); crosses the see of Galilee (John 6:1 – there being no indication that he has left Jerusalem); walks in Galilee, being unable to walk in Judaea (John 7:1 – because the Jews were seeking to kill him, though he had not been in Jerusalem since John 5:47). If the suggested emendation is made the course of events is a follows: Jesus is in Galilee (John 4:54), crosses the sea (John 6:1), goes up to Jerusalem (John 5:1), and returns, for security, to Galilee (John 7:1).

(3) John 7:15-24 should be read after John 5:47. It continues the argument of chapter 5, and interrupts the connection between John 7:14 and John 7:25.

(4) John 10:19-29 should be read after John 9:41. The σχισμα of John 10:19 follows naturally upon the miracle of chapter 9, and so does the remark of John 10:21. Further, John 10:18 is admirably taken up by John 10:30.

(5) Chapters 15 and 16 should be taken at some point before John 14:31, which closes the upper-room discourses. The order adopted by Bernard is John 13:1-31a; John 15:1-27; John 16:1-33; John 13:31-38; John 14:1-31.

Wilbert Francis Howard, C. K. Barrett, The Fourth Gospel in Recent Criticism and Interpretation, Wipf and Stock; 4th ed. edition, 2009

Every fresh attempt to show by what different hands the various parts of the Gospel were written adds to the inherent improbability that any solution will be found along these lines. There are too many cross-divisions. Some start from the Prologue, some form the Appendix, others from chap. Vii., others, again, from the Farewell Disclosure. To some there is a clear line of demarcation between discourses and narratives, for others the dividing line cuts across both. Sometimes the seeming contradictions or repetitions are a clear token that separate hands have taken part in the composition of the Gospel. At other times we are assured that the chronological scheme is manifestly a later device. Now it is evident that, if the Gospel is a composite work, the validity of these various criteria will be shown by the convergence of their evidence toward one definite result. (P.97)

The literary unity of the Fourth Gospel has been challenged upon the ground that a careful reading of the text reveals numerous seams and sutures. The force of this argument has been greatly reduced by the general recognition that several considerable displacements have taken place in the text. (P.110)

In several places internal evidence raises a strong suspicion that sections of the gospel (John) are not in the right order. A growing weight of opinion finds the explanation in a theory of displacement of leaves. Some attribute this to an accident which could be further manuscript after the writer’s death, and the carelessness of the editor who regrouped the scattered leaves. Others, with greater probability, think that the writer left his manuscript in perfectly arranged, and the reference in which he was held by his disciple prevented any change in the manuscripts as it had been left, beyond a few words here and there. The discovery that, in several of the passages where rearrangement is required on internal grounds, the displaced sections are, as regards length, multiples of a fixed unit has done much to remove this hypothesis from the class of capricious and subjective speculation. (pp. 160-161)

The discovery of the Sinaitic Syriac version of the gospels.. started suggestions that textural dislocation had taken place at a very early stage in the history of the text of the Fourth gospel… Many varieties and rearrangements have been proposed by different scholars. (p. 111)

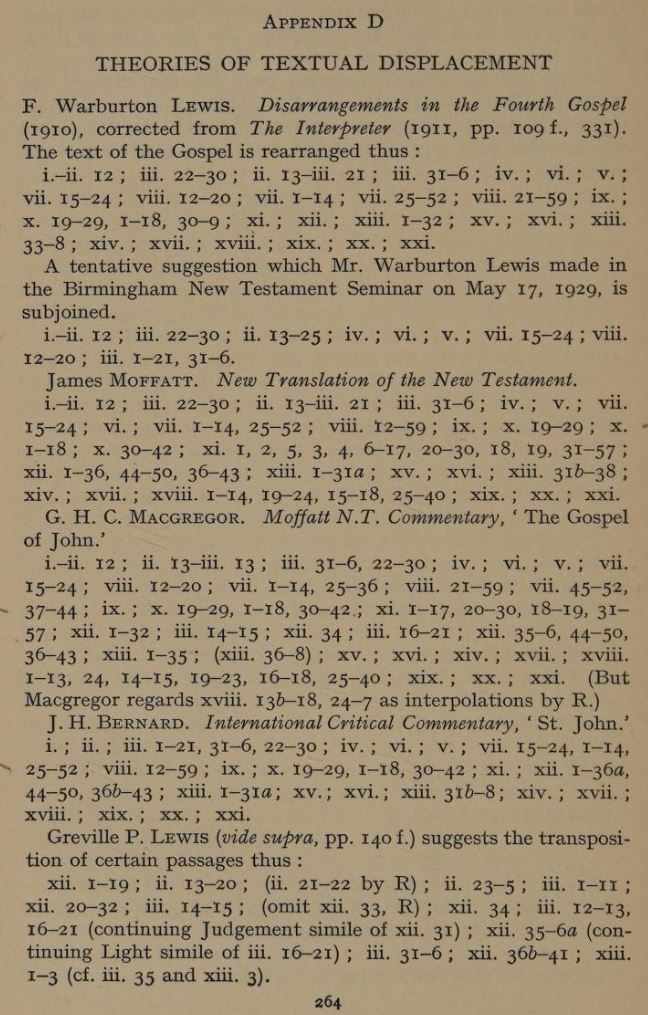

A glance at the table of proposed rearrangements in appendix D will show what a large measure of agreement there is amongst those writers who are convinced that the present order of the sections in the Fourth Gospel (John) does not agree with the intention of the Evangelist himself. The questions which arise in the mind of the student of the gospel are these: (1) do these discontinuities in narrative or discourse point to some primitive dislocation of the text and is this suspicion supported by any objective test. (2) is there any other probable explanation of the manifestly disordered state of the text (3) what bearing will our answer have upon the further question of the worth of the chronological data provided in the gospel. (p. 114)

General agreement that our present text of this gospel is disordered in many places by no means involves agreement as to the cause one of the most observations in B. W. Bacon’s keen analysis is that at every point where dislocation is evident, a Redactor can be traced. To quote his words exactly, “in every case these displacements occur in conjunction with passages which by the direct connection with the Appendix (Chapter 21) or otherwise give independent evidence is having been introduced by R (Redactor).” (PP.117-118)

We shall see presently that there is a case for suspecting that the whole Nicodemus episode has been misplaced and we must therefore take note of the very confused phraseology in which the next section begins…Other examples might be given to show that not only considerations of subject matter, but slight disturbances in the text, suggest to us that some displacement has taken place. If the disarrangement is merely the result of accident, not only in the original separation of leaves, but in their fresh grouping, we should not expect these signs of editorial handiwork. If, however, we postulate an editor who carefully rearranged the disturbed leaves, we are left astonished at his singular ineptitude in leaving such an obvious misfit as the present position of chapter 5. But this difficulty becomes all greater if the disturbance of the text is due to the deliberate work of a systematic Redactor, who went right through the gospel, inserting Synoptic material or considerable passages to suit his own ends in winning ecclesiastical sanction, either by rehabilitating Peter or by suggesting Apostolic authorship. (P.118)

There are many signs that the gospel was not left in the form of a finished work. There are also indications that the writer went over his rough draft adding fresh incidents or meditations, inserting comments, elaborations, reconsiderations. It is in this way, probably, that we attain an understanding of the otherwise perplexing interruptions in the thought and rhyme of the Prologue, and the duplications and, as some have said, the inconsistencies of the Farewell Discourse. It has often been observed that the sequence of thought and the prologue runs smoothly if the verses relating to John the Baptist are omitted (John 1:6-8, 15). If these verses originally came immediately before verses 19, they would form an opening for the gospel not unlike the beginning of Mark. When the prologue was written and prefixed to the rough draft of the gospel, these verses may well have been detached from their former position and inserted into the prologue to emphasize the subordination of the Baptist, or to bring his witness into prominence. (P.118)

James Moffatt’s Translation of the Bible

“The arrival of the twentieth century marked the beginning of modern speech version. The archaeological discovery of secular Greek papyri in the sands of Egypt convinced biblical scholars that the Bible was originally written in the language of its day, and this in turn encouraged scholars to translate Scripture into contemporary English. James Moffatt (1870-1944), a Scotsman, published a modern speech version in 1928, after moving to America. Called ‘A New Translation of the Bible,’ the final version appeared in 1935. Between the two world wars, Moffatt’s Bible was the most popular modern-speech version in America.” (David Ewert, Dictionary of Christianity in America, IVP, 1990)

Given the developments of Bible translation in the latter half of the twentieth century, James Moffatt’s A New Translation of the Bible might well be called the “grandfather” of the modern-language Bible in English. Regardless of one’s theological stance, Moffatt’s work is admirable as a prodigious work of scholarship and creativity produced in a remarkably short period of time by one person. (The Bible: James Moffatt Translation, Harper San Francisco, 2004, Publisher’s Preface)

Moffatt, One of the pioneers of the shape modern biblical scholarship was taken—a focus on both grammar and history—James Moffatt was among the first scholars to approach the biblical text seeking to illuminate the historical background of the Bible and to combine that understanding with a grasp of the literary features in the context of faith. Moffatt produced his translation of the New Testament while he was serving as Professor of Greek and New Testament Exegesis at Oxford, and its reception was so favorable that he undertook the Old Testament in order to produce a complete Bible. The version is highly colloquial, and allows the reader to quickly follow the progress of thought in many passages (especially in the Epistles) where a more literal rendering makes for difficult going.

James Moffatt’s New Testament Translation

James Moffatt transposed sections of John according to what he thought was their true position.

The New Testament: A New Translation

James, Moffatt, New York : Hodder and Stoughton : G.H. Doran, 1913

Internet Archive Link: https://archive.org/details/newtestamentnewt01moff/page/112/mode/2up

Preface to the New Testament Translation (Abridged):

Hellenistic Greek has its own defects, from the point of view of the classical scholar, but it is an eminently translatable language, and the evidence of papyrology shows it was more flexible than once was imagined. My intention, therefore, has been to produce a version which will to some degree represent the gains of recent lexical research and also prove readable. I have attempted to translate the New Testament exactly as one would render any piece of contemporary Hellenistic prose; in this way, students of the original text may perhaps be benefited. But I hope also that the translation may fall into the hands of some who know how to freshen their religious interest in the meaning of the New Testament by reading it occasionally in some unauthorized English or foreign version, as well as into the hands of others who for various reasons neglect the Bible even as an English classic. This is a hope which, no doubt, is accompanied with some risks and fears. Every translation has to face a double ordeal. Some of its readers know the original, some do not, and both classes have to be met. ” The English reader,” as Dr. Rouse remarks, ” may be quite competent to judge of a translation as literature and as intelligible or not intelligible, but he cannot judge of its accuracy. The scholar alone can judge of its accuracy, but (granting that he has literary taste) he knows the original too well to be independent of it, and hence cannot judge of the impression which the translation will make on the minds of those who are not scholars.”

I wish only to add this caution, that a translator appears to be more dogmatic than he really is. He must come down on one side of the fence or on the other. He has often to decide on a rendering, or even on the text of a passage, when his own mind is by no means clear and certain. In a number of cases, therefore, when the evidence is conflicting, I must ask scholars and students to believe that a line has been taken only after long thought and only with serious hesitation.

The translation has been made from the text recently issued by Von Soden of Berlin, but I have not invariably followed his arrangement and punctuation. Wherever I have felt obliged to adopt a different reading, this is noted at the foot of the page.

Quotations or direct reminiscences of the Old Testament are printed in italics.

The books are arranged for the convenience of the general reader in the order of the English Bible. This applies to the order of chapters as well. Thus the last four chapters of Second Corinthians appear in their usual canonical position instead of in what I believe to be their original position between First and Second Corinthians. The only exception I have made to this rule is in the case of some occasional transpositions either of verses or of paragraphs, for example, in the case of the Fourth Gospel. Anyone who cares to look into the evidence for such changes will find it in my Introduction to the Literature of the New Testament, (James Moffatt, An introduction to the literature of The New Testament, Edinburgh : T. & T. Clark, 1918, Internet Archive Link: https://archive.org/details/introductiontoli00moffuoft/page/550/mode/2up)

Lastly, it is right to add that I have not consulted any other version of the New Testament in preparing this work, though probably echoes and reminiscences have clung to one’s mind. The only version I have kept before me is the one I prepared thirteen years ago for my Historical New Testament. But the present version is not a revision of that. It is an independent work. I agreed to undertake it with sharp misgivings, but I trust that the spirit and method of its composition may at any rate do something to make some parts of the New Testament more intelligible to some readers.

About James Moffatt

James Moffatt, (born July 4, 1870, Glasgow, Lanarkshire, Scot.—died June 27, 1944, New York, N.Y., U.S.), Scottish biblical scholar and translator who singlehandedly produced one of the best-known modern translations of the Bible.

Educated at Glasgow Academy and Glasgow University, Moffatt was ordained in the Church of Scotland in 1896 and immediately began a career of pastoral service that was to last 16 years, during which time he produced his first scholarly writings. His Introduction to the Literature of the New Testament, a comprehensive survey of contemporary biblical scholarship, appeared in 1911, while he was pastor of a church at Broughton Ferry, Scot. The next year he joined the faculty at the University of Oxford and in 1913 published his translation of the New Testament. From 1915 to 1927 he was a professor of church history at the University of Glasgow, publishing his Old Testament in 1924, and in 1927 he took a similar position at Union Theological Seminary in New York City. Although his own chief interest was in church history, he is better known for his New Testament criticism; he edited a series of commentaries on the New Testament, published 1928–49. After his formal retirement in 1938, he continued teaching and served as a consultant to a radio serial dramatization of the Bible.

His New Translation of the New Testament was first published in 1913. His New Translation of the Old Testament, in two volumes, was first published in 1924. The Complete Moffatt Bible in one volume was first published in 1926. It was completely revised and reset in 1935. A Shorter Version of the Moffatt Translation of the Bible was first published in 1941.

The Moffatt New Testament Commentary, based on his translation, has 17 volumes. The first volume was published in 1928, and the final volume in 1949. The concordance of the complete Bible was first published in 1949. Moffatt later served as executive secretary of the committee of translators for the Revised Standard Version.

Notable Works of James Moffatt include the following:

- The Historical New Testament: Being the Literature of the New Testament Arranged in the Order of its Literary Growth and According to the Dates of the Documents, 1901, https://archive.org/details/historicalnewtes00moffrich/page/n5/mode/2up

- The Golden Book of John Owen: Passages from the Writings of the Rev. John Owen, 1904

- Literary Illustrations of the Bible: The Book of Ecclesiastes, 1905

- Literary Illustrations of the Bible: The Gospel of Saint Mark, 1905

- Literary Illustrations of the Bible: The Epistle to the Romans, 1905

- Literary Illustrations of the Bible: The Book of Revelation, 1905

- Literary Illustrations of the Bible: The Gospel of Saint Luke, 1906

- Literary Illustrations of the Bible: The Books of Judges and Ruth, 1906

- The Literal Interpretation of the Sermon on the Mount, (with Marcus Dods and James Denney) 1904 (Re-published 2016, CrossReach Publications)

- The Mission and Expansion of Christianity in the First Three Centuries, v. 1–3 by Adolf Harnack. Translated by James Moffatt (1908)

- Paul and Jesus, 1908

- George Meredith: Introduction to His Novels, 1909

- The Life of John Owen, 1910?

- Paul and Paulinism, 1910, https://archive.org/details/paulpaulinism00moffuoft/page/n5/mode/2up

- The Second Things of Life, 1910

- The Expositor’s Dictionary of Texts, vol. 1: Genesis to the Gospel of St. Mark, 1910

- The Expositor’s Dictionary of Texts, vol. 2: The Gospel of St. Luke to Revelation, 1911

- Reasons and reasons, 1911

- An Introduction to the Literature of the New Testament, 1911, https://archive.org/details/introductiontol00moff/page/n5/mode/2up

- The Theology of the Gospels, 1912

- The Expositor’s Dictionary of Poetical Quotations, 1913

- The Moffatt Translation of the New Testament, 1913, https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.264535/mode/2up

- A Book of Biblical Devotions for Members of the Scottish Church, 1919

- The Approach to the New Testament, 1921, https://archive.org/details/heapproachtothen00moffuoft/page/n5/mode/2up

- The Spiritual Pilgrimage of Jesus, (with James Alex Robertson) 1921

- Jesus on Love to God, Jesus on Love to Man, 1922

- The Moffatt Translation of the Old Testament, 1924, https://archive.org/details/oldtestamentnewt0000unse/page/n5/mode/2up

- The Bible in Scots Literature, 1924

- The Tree of Healing. Short Studies in the Message of the Cross, (With a biographical sketch by James Moffatt) 1925

- The Presbyterian Churches, 1928

- Love in the New Testament, 1929

- The Moffatt New Testament Commentary on the Bible V.1, 1929

- The Day Before Yesterday, 1930

- Grace in the New Testament, 1932

- He and She: A Book of Them, 1933

- His Gifts & Promises: Being Twenty-Five Reflections and Directions on Phases of our Christian Discipline, From the Inside., 1934

- Handbook to the Church Hymnary, with Supplement, (with Millar Patrick) 1935

- The Ideas Behind the Moffatt Bible: Compiled from the Introduction to the Moffatt Bible, 1935

- The Second Book of He and She: Another Book of Them, 1935

- An Approach to Ignatius, 1936

- The First Five Centuries of the Church, 1938

- Jesus Christ the Same; The Shaffer Lectures for 1940 in the Divinity School of Yale University, 1940

- The Thrill of Tradition, 1944 https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.60947/page/n7/mode/2up

- Concordance of The Moffatt Translation of the Bible, 1949